Research topics

Fashioning Sudan is centered around the general topics of identity and appearance, and how these two concepts were build and negotiated together by past societies.

The project embraces three different ways in which humans experience ‘identity’: we craft and perform our own identities, while recognising the identities of others. Archaeological work consists of bridging these gaps between past and present, others and ourselves. Fashioning Sudan will structure research according to these three paradigms.

Our main postulate is to recognise dress practices as a tangible and intimate gateway to past populations and their identities, as garments followed an individual from birth to death as a second skin. “Dress” includes all manner of body protection and ornamentation created by humankind: clothing, hairstyles, jewellery, tattoos, and scarification. When combined according to specific cultural codes, these elements form “dress practices” functioning as powerful means of non-verbal communication and “dressing” the body into an individual and social persona.

The first theme, “Recognising identities” will propose a new paradigm to study and use dress practices as identity markers. It will lay the methodological and theoretical groundwork of the project, providing a solid framework for subsequent research and situating future results within current debates in archaeology and the Humanities in general. The main questions addressed will be:

- Can we use iconography to access questions of identity, and if yes, how?

- How can we decolonise our approach to ‘cultural identity’ in ancient Sudan?

- Which theories can we use to examine the entanglements of garments, people, and the Sudanese environment?

- How can we build new ontological categories based on these concepts and incorporating ancient Sudanese dress practices in their socio-cultural milieu?

The Work Package will follow a strong theoretical approach based on the concepts of materiality, entangled networks, and sensory assemblages developed in archaeology and social anthropology, incorporating recent developments in the decolonisation of cultural heritage. This body of theories will be assembled and discussed through literature study, team meetings, and thematic workshops organised with our advisory expert group. Several paradigms, such as craft transmission or sensory experience, will be tested through experimental archaeology and garment reconstructions (both physical garments and 3D digital illustrations). The aim is to create a cohesive theoretical model for dress practices on which to rest our methodology of research, analyses, and interpretations. This model will sustain the creation of new ontological categories, which will question traditional taxonomies employed in fashion history and develop a typology of garments specific to the Sudanese milieu. This phase will be conducted throughout the building of a relational database grouping textile, skin, and leather archaeological items, together with a selection of iconographic documents and body adornments (hairstyles, accessories, jewellery, body modifications such as tattooing and scarification). Populating the database will result in the identification of garment types and typical traits of clothing cultures, such as actual items (e.g. the loincloth), specific aesthetics (e.g. fringes) or techniques (e.g. openworks), and concepts (e.g. reveal/conceal the body).

The theme “Crafting identities” will explore the manufacturing of dress components in their cultural and natural environment. It will consist of examining and understanding the mechanisms that led specific raw material to be transformed into garments. It will lead to the identification of raw material usage through time and space, and to the understanding of the socio-economic and cultural models behind this selection. The main questions addressed will be:

- What plant and animal products were used to make garments and what are their characteristics?

- How were fibres procured and prepared?

- What was the chaîne opératoire of garment production? How did it change through time and space?

- How did garment production affect the economy? Does it reflect specific modes of subsistence?

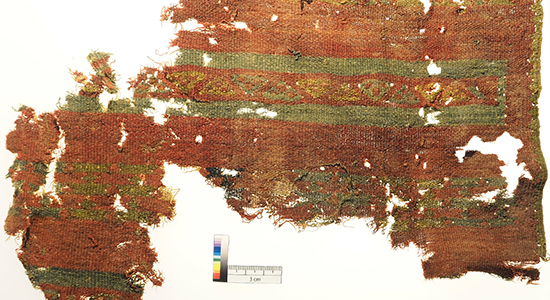

This Work Package will merge the study of ancient crafts with economy, drawing data from the artefacts themselves as well as from tools, archaeobotany, archaeozoology, landscape archaeology, the study of the chaîne opératoire, experimental archaeology, and textual sources. The manufacture of garments necessitated the exploitation of varied raw resources, sometimes hard to produce or procure, and the mobilisation of a large workforce involved in countless, enormously time-consuming operations. Three stages can be identified: the production of resources (e.g. cultivating plant fibres, gathering wild grasses, hunting wild animal, maintaining animal husbandry), their transformation into usable material (e.g. by harvesting, shearing, skinning, washing/retting, combing, curing, tanning, spinning, etc.), and the final manufacturing (e.g. weaving, cutting, tailoring, dyeing, sewing, decorating, washing, repairing, etc.). The identification and study of these different aspects of garment production will bring entirely new information on the economy of ancient Sudan, for the first time addressing the domain of nonsubsistence and comfort items. It will also reveal different production models usually overlooked in the archaeological record of non-prehistoric periods, such as hunting and gathering, or nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralism, and observe their relations to sedentary agriculture. The study of craft techniques and apprenticeship will also shed an original light on the savoir-faire and social meanings of craft and garment production. The recognition of these mechanisms through the history and vast territory of ancient Sudan will lead to the identification of cultural and trading networks. Together, this broad range of data will participate in unveiling key aspects of past Sudanese and Nubian identities: how people related to the natural surroundings, how they shared knowledge and products, how they organised their everyday activities and sustained their livelihood, and finally, how they structured their relationships with neighbouring communities. Tracking the use of raw resources through time and space will involve sampling of both textile and skin items, fibre and skin identification (imaging with a Scanning Electron Microscope, palaeoproteomics, HPLC analyses for the identification of dyeing and tanning agents), as well as radiocarbon dating.

The last theme will focus on “Performing identities” and relate dress practices to the individual and social body. It will aim at understanding the phenomenon of dress practices as a whole: how it developed, and how it structured the construction of self and group identities. The main questions will be:

- What type of garment was used in specific periods, locations, and contexts?

- How did garments function, materially, as body coverings, and sociologically, as means of communication?

- How was dress used in the building of different identities (age, gender, social status, occupation, etc.)?

- How did dress practices react to social changes and changing attitudes towards the body?

These questions will be addressed through the combination of archaeology, craft studies, textile and leather experiments, history, iconography, and textual research, thanks to the tools and theoretical models built previously. The first part of this third Work Package will draw statistical analyses from the database, revealing and tracing the use and distribution of different dress components through time and space. The results will be assembled in a synchronic and diachronic map of dress practices throughout the Kushite world. The second part of WP3 will study the process of identity building through dress, on the scale of both individuals and communities. Particular attention will be devoted to revealing different attitudes towards the body and assessing the recurrence – or absence thereof – of specific costumes for specific groups. The goal of WP3 is not to assemble the blocks of a rigid typology, assigning clothing traditions to specific time frames or, worse, ethnic groups. On the contrary, we believe in the coexistence in ancient Sudan of multiple ‘groups’ and multi-layered narratives of identity, which combination or exclusion constantly evolved through peoples’ lifetime. Examples of partial identities currently visible in the record can be archers, unmarried girls, religious officials, or children. Fashioning Sudan will particularly focus on gender and age, social status, bodies in life and death, regional identities, and individuals vs. groups. Using data acquired and analysed in detailed case-studies, we will attempt to trace dynamics of relationships and exchanges between people and cultural horizons.